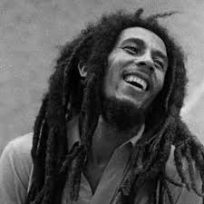

Bob Marley

Bob Marley was reggae’s foremost practitioner and emissary, embodying its spirit and spreading its gospel to all corners of the globe. His extraordinary body of work embraces the stylistic spectrum of modern Jamaican music—from ska to rock steady to reggae—while carrying the music to another level as a social force with universal appeal. Marley cannot claim to have had even one hit single in America, but few others changed the musical and cultural landscape as profoundly as he. As Robert Palmer wrote in a tribute to Marley upon his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, “No one in rock and roll has left a musical legacy that matters more or one that matters in such fundamental ways.”

There’s no question that reggae is legitimately part of the larger culture of rock and roll, partaking of its full heritage of social forces and stylistic influences. In Marley’s own words, “Reggae music, soul music, rock music—every song is a sign.” Marley’s own particular symbolism derived from his beliefs as a Rastafarian—a sect that revered Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia (a.k.a. Ras Tafari) as a living god who would lead oppressed blacks back to an African homeland—and his firsthand knowledge of the deprivations of the Jamaican ghettos. His lyrics mixed religious mysticism with calls for political uprising, and Marley delivered them in a passionate, declamatory voice.

Reggae’s loping, hypnotic rhythms carried an unmistakable signature that rose to the fore of the music scene in the Seventies, largely through the recorded work of Marley and the Wailers on the Island and Tuff Gong labels. Such albums as Natty Dread and Rastaman Vibration endure as reggae milestones that gave a voice to the poor and disfranchised citizens of Jamaica and, by extension, the world. In so doing, he also instilled them with pride and dignity in their heritage, however sorrowful the realities of their daily existence. Moreover, Marley’s reggae anthems provided rhythmic uplift that induced what Marley called “positive vibrations” in all who heard it. Regardless of how you heard it—political music suitable for dancing, or dance music with a potent political subtext—Marley’s music was a powerful potion for troubled times.

Marley was born on Jamaica to a young black mother and an older white father. A precocious musician, a teenaged Marley formed a vocal trio in 1963 with friends Neville “Bunny” O’Riley Livingston (later Bunny Wailer) and Peter McIntosh (later Peter Tosh). The group members had grown up in Trench Town, a ghetto neighborhood of Kingston, listening to rhythm and blues on American radio stations. They heard such R&B mainstays as Ray Charles, the Drifters, Fats Domino and Curtis Mayfield. They took the name the Wailing Wailers (shortened to the Wailers) because they were ghetto sufferers who’d been born “wailing.” As practicing Rastas, they grew their hair in dreadlocks and smoked ganja (marijuana), believing it to be a sacred herb that brought enlightenment.

The Wailers recorded prolifically for small Jamaican labels throughout the Sixties, during which time ska—Jamaican dance music that drew from African rhythms and New Orleans R&B—was the hot sound. The Wailers had their first hit in 1963 with “Simmer Down,” and they went on to record 30 sides in the “rude boy” ska style for Jamaican soundman Coxsone Dodd’s Studio One. By this time, Marley’s preoccupations were taking a spiritual turn, and Jamaican music itself was changing from the bouncy ska beat to the more sensual rhythms of rock steady. An association with Jamaican producer Lee Perry resulted in some of the Wailers’ memorable recordings, including “Soul Rebel” and “Duppy Conqueror,” and the albums Soul Rebel and Soul Revolution.

Though the Wailers were popular in Jamaica, it was not until the group signed with Chris Blackwell’s Island Records in the early Seventies that they found an international audience. Their first recordings for Island, Catch a Fire (1972) and Burnin’ (1973), were hard-hitting albums full of what critic Robert Christgau called Marley’s “melodic propaganda.” The latter contained “I Shot the Sheriff.” Reggae aficionado Eric Clapton’s version of the song went to #1 in 1974, which further carried the name of Marley and the Wailers beyond their Jamaican home base.

With the departure of founding members Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer after Burnin’, Marley took center stage as singer, songwriter and rhythm guitarist. Backed by a first-rate band and the I-Threes vocal trio—which included his wife, Rita—Marley rose to the occasion with 1975’s Natty Dread (his first album to chart in America) and the string of politically charged albums that followed. These included Rastaman Vibration, his highest-charting album (1976, #8); the fiery, oratorical Exodus (1977, #20); the mellow, herb-extolling Kaya (1978, #50), the live double-album Babylon by Bus (#1978, #102), and the politicized, defiant Survival (1979, #70) and Uprising (1980, #46). Uprising was the last studio album released during Marley’s lifetime.

So influential a cultural icon had Marley become on his home island by the mid-Seventies that Time magazine proclaimed, “He rivals the government as a political force.” On December 5, 1976, Marley was scheduled to give a free “Smile Jamaica” concert, aimed at reducing tensions between warring political factions. Two days before the scheduled concert, he and his entourage were attacked by gunman. Though Bob and Rita Marley were grazed by bullets, they electrified a crowd of 80,000 people when both took to the stage with the Wailers on the 5th—a gesture of survival that only heightened Marley’s legend. It further galvanized his political outlook, resulting in the most militant albums of his career: Exodus, Survival and Uprising.

He was particularly moved throughout his career by the gulf between haves and have-nots, a culture of oppression that was particularly glaring in his poverty- and crime-ridden Jamaican homeland. “We should all come together and creative music and love, but [there] is too much poverty,” Marley told writer Timothy White in 1976. “The most intelligent people [are] the poorest people…[but] people don’t get no time to feel and spend [their] intelligence…The intelligent and innocent are poor, are crumbled and get brutalized. Daily.”

Given the violent culture that he survived and transcended, Marley’s death seems almost cruelly flukish. In 1977, surgeons removed part of a toe that had been injured in a soccer game, upon which a cancerous growth was found. This led to the discovery of spreading cancer in 1980, after Marley collapsed while jogging in Central Park, that claimed his life less than a year later. Though he died prematurely at age 36, the heartbeat reggae rhythms of the enormous body of music that Bob Marley left behind have endured. Moreover, Jamaica itself has been transformed by his charismatic personality and musical output. Marley was buried on the island with full state honors on May 21, 1981. In a crowning irony, given the reviled status that Rastafarians and their music had once suffered at the hands of the Jamaican government, Marley’s pacifist reggae anthem, “One Love,” was adapted as a theme song by the Jamaican Tourist Board. Meanwhile, Marley’s music continues to find an audience. With sales of more than 10 million in the U.S. alone, Legend—a best-of spanning the Island Records years (1972-1981)—remains the best-selling album by a Jamaican artist and the best-selling reggae album in history.