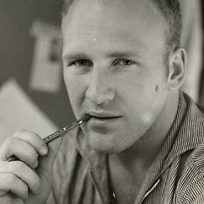

Ken Kesey

Ken Kesey, the psychedelic pioneer who wrote the 1960s novels, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and “Sometimes a Great Notion,” and who became famous as a counterculture figure leading his LSD-fueled Merry Pranksters on a cross-country bus ride, died Saturday following liver cancer surgery.

Kesey died at Sacred Heart Medical Center in Eugene, Oregon, two weeks after surgery to remove 40 percent of his liver. Kesey, who was 66, “passed away peacefully in his sleep” with his family at his side, according to a nursing supervisor. His liver cancer had been complicated by diabetes and a minor stroke he suffered four years ago. “He’s gone too soon and he will leave a big gap. Always the leader, now he leads the way again,” said Ken Babbs, a longtime friend. After studying writing at Stanford University, Kesey burst onto the literary scene in 1962 with “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” followed quickly with “Sometimes a Great Notion” in 1964, then went 28 years before publishing his third major novel.

In 1964, he rode across the country in an old school bus named Furthur driven by Neal Cassady, hero of Jack Kerouac’s Beat Generation classic, “On The Road.” The bus was filled with pals who called themselves the Merry Pranksters and sought enlightenment through the psychedelic drug LSD. The odyssey was immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s 1968 account, “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.” “Anyone trying to get a handle on our times had better read Kesey,” Charles Bowden wrote when the Los Angeles Times honored Kesey’s lifetime of work with the Robert Kirsh Award in 1991. “And unless we get lucky and things change, they’re going to have to read him a century from now too.”

Hated Film of “Cookoo’s Nest”

“Sometimes a Great Notion,” widely considered Kesey’s greatest book, told the saga of the Stamper clan, rugged independent loggers carving a living out of the Oregon woods under the motto, “Never Give a Inch.” It was made into a movie starring Henry Fonda and Paul Newman.

But “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” became much more widely known, thanks to a movie that Kesey hated. It tells the story of Randle P. McMurphy, who feigned insanity to get off a prison farm, only to be lobotomized when he threatened the authority of the mental hospital. The 1974 Milos Forman movie swept the Academy Awards for best picture, best director (Forman), best actor (Jack Nicholson) and best actress (Louise Fletcher), but Kesey sued the producers because it took the viewpoint away from the character of the schizophrenic Indian, Chief Bromden. Kesey based the story on experiences working at the Veterans Administration hospital in Palo Alto, Calif., while attending Wallace Stegner’s writing seminar at Stanford. While Kesey continued to write a variety of short autobiographical fiction, magazine articles and children’s books, he didn’t produce another major novel until “Sailor Song” in 1992, his long-awaited Alaska book, which he described as a story of “love at the end of the world.” “This is a real old-fashioned form,” he said of the novel. “But it is sort of the Vatican of the art. Every once in a while you’ve got to go get a blessing from the pope.”

Psychedlic Prankster

Kesey considered pranks part of his art, and in 1990 he took a poke at the Smithsonian Institution by announcing he would drive his old psychedelic bus to Washington, D.C., to give it to the nation. The museum recognized the bus as a new one, with no particular history, and rejected the gift.

In a 1990 interview with The Associated Press, Kesey said it had become harder to write since he became famous. “When I was working on ‘Sometimes a Great Notion,’ one of the reasons I could do it was because I was unknown,” he said. “I could get all those balls in the air and keep them up there and nothing would come along and distract me. Now there’s a lot of stuff happens that happens because I’m famous. And famous isn’t good for a writer. You don’t observe well when you’re being observed.” A graduate of the University of Oregon, Kesey returned to his alma mater in 1990 to teach novel writing. With each student assigned a character and writing under the gun, the class produced “Caverns,” under the pen name OU Levon, or UO Novel spelled backward. “The life of it comes from making people believe that these people are drawing breath and standing up, casting shadows, and living lives and feeling agonies,” Kesey said then. “And that’s a trick. It’s a glorious trick. And it’s a trick that you can be taught. It’s not something, just a thing that comes from the muses.”

Fond of Performing

Among his proudest achievements was seeing “Little Tricker the Squirrel Meets Big Double the Bear,” which he wrote from an Ozark mountain tale told by his grandmother, included on the 1991 Library of Congress list of suggested children’s books. “I’m up there with Dr. Seuss,” he crowed. Fond of performing, Kesey sometimes recited the story in top hat and tails accompanied by an orchestra, throwing a shawl over his head while assuming the character of his grandmother reciting the nursery rhyme, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

Other works include “Kesey’s Garage Sale” and “Demon Box,” collections of essays and short stories, and “Further Inquiry,” another look at the 1964 bus trip in which the soul of Cassady is put on trial. “The Sea Lion,” another children’s book, told the story of a crippled boy who saves his Northwest Indian tribe from an evil spirit by invoking the gift-giving ceremony of potlatch. Kesey, also given credit for turning the legendary rock band the Grateful Dead on to LSD, continued to write until going in for surgery two weeks ago, said a friend, Philip Dietz, who calls himself “the last Prankster.” “We’d get together on the weekends and play the Thunder Machine,” said Dietz, who lives near Kesey and his family farm in Pleasant Hill, Oregon. The Thunder Machine, an amalgam of an old Thunderbird fender, piano strings, a smoke machine and other mixing gear, was a touchstone for Prankster jam sessions and has been featured in Grateful Dead concerts. Kesey was also working on turning film footage of the Furthur odyssey into a trio of movies, and he was fascinated by the promise that the Internet could be used as a kind of “pirate” medium to broadcast performance art and bypass publishing houses.

Eearly Years

Born in La Junta, Colo., on Sept. 17, 1935, Kesey moved in 1943 from the dry prairie to his grandparents’ dairy farm in Oregon’s lush Willamette Valley. He earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Oregon, where he also was a wrestler. Kesey encountered drugs in 1959 when, as a struggling writer studying at Stanford University, he signed up for experiments at the Menlo Park Veterans Administration Hospital to test the effects of LSD and other hallucinogens. After serving four months in jail for a marijuana bust in California, he set down roots in Pleasant Hill in 1965 with his high school sweetheart, Faye, and reared four children. Their rambling red barn house with the big Pennsylvania Dutch star on the side became a landmark of the psychedelic era, attracting visits from myriad strangers in tie-dyed clothing seeking enlightenment. The bus Furthur rusted away in a boggy pasture while Kesey raised beef cattle.

Pranksters Sticking Together

Kesey died just a week after fellow Prankster Sandy Lehmann-Haupt, who passed away of a heart attack at age 59. In a recent interview, Kesey had said the Pranksters “still stick pretty close together.” “When you don’t know where you’re going, you have to stick together just in case someone gets there,” he said. Kesey was diagnosed with diabetes in 1992. His son Jed, killed in a 1984 van accident on a road trip with the University of Oregon wrestling team, was buried in the back yard at Pleasant Hill. Kesey is survived by his wife, Faye; his son, Zane; his daughters, Shannon and Sunshine, and three grandchildren.

“Saying Goodbye”

Zane Kesey said the author spent a last afternoon on Monday at his farm in Pleasant Hill. “He was doing really well and he came home,” he said. “It was a beautiful day and he just walked around, then he lay down on his back on the porch and looked up at the sky for a while. It was like he was saying goodbye.” “He had a full life, that’s for sure. He didn’t just sit around,” said Zane Kesey, who is 40. Ken Kesey died with a major project in the works, a film taken during the Pranksters bus trip. Two parts have been finished and were being sold through Kesey’s website. His son also said Kesey had several unpublished works, including the completion to his partially published “Seven Prayers of Grandma Whittier” and a book he wrote while he was in jail for four months for a marijuana bust in the mid-60s. His son said “he was always writing. He was the total archivist.” When asked in a recent interview if he had any regrets about his colorful past, Kesey replied: “Anybody who says they have no regrets is either a dimwit or a liar – probably both.”